Mechanical and Civil Engineer

He had 15 siblings, and my great-great-grandmother was one of them.

1820 April 30 Daniel was born in Shildon, probably at the Grey Horse Inn. His parents were Daniel Adamson (farmer and publican) and Nanny Gibson. He was the 13th of their 16 children. [1]

1833 April 30 On this day, his 13th birthday he left the Edward Walton Quaker School and four days later began his apprenticeship at the Stockton and Darlington Railway works in Shildon under the wing of Timothy Hackworth.

1845 June 10 Daniel married Mary Pickard at the parish church Aysgarth, in Wensleydale. "Rank or Profession" of both of their fathers is recorded as "Farmer". From various census returns it is clear that Mary was born in Danby Wiske, which is a village near Northallerton. [2]

1846 Q4 Alice Ann his first child was born in Shildon

1850 July 7 Daniel's employer Timothy Hackworth died, and later Hackworth's engine works was sold [6]. So it appears that in anticipation of major changes in Shildon Daniel decided to to spread his wings, and having risen to the level of general manager at the engine works he removed to Stockport to take up the post of manager of Heaton Foundry which was on the corner of Gordon Street, Lancashire Hill, Stockport.

1851 Jan 24 Lavinia his second child was born at 1 Appleton's Terrace [aka Appleton Court], Nicholson Street, off Lancashire Hill Stockport. [2] The house was a very modest abode, probably what is known as a two-up-and-two-down with a steep embankment at the end of the back-yard. Now [2010] Nicholson Street has been cleared of the Victorian properties but the cobbled street is still there. On the crest of the embankment there now stands Pendlebury Hall, originally an ophanage; later Stockport Technical School coincidentally the webmaster's alma mater; and now, today the place is a Care Home for the elderly.

1852 In the spring Daniel moved to Ashton, Cheshire to set-up as an iron-master on his own account. The works, his first, became the Newton Moor Iron Works and was north-east of the junction of Talbot Road and Ashton Road, Dukinfied, Cheshire.

1861 In the Census and aged 41 he is described as an engineer employing "128 men and boys"; and "2 farm-men". Residence believed to have been Goodier House, Back Lane, Newton, Hyde [7]. Present were his wife Mary, and daughters Alice-Ann and Lavinia.

1867 CHRISTMAS DAY o o o o Daughter Alice (21) and sister Lavinia (16) were baptised at St.Mary's, Newton-in-Mottram, Cheshire. Coincidentally, Lavinia died on Christmas Day in 1925. (see also 1851). The church is still there on Talbot Road.

1871 In the Census Daniel is described as a Civil and Mechanical Engineer "employing 250 workmen at Newton Moor Iron Works".

1874 Due to lack of space he re-established his business on a new site about a quarter mile to the north, at Johnsonbrook Rd.

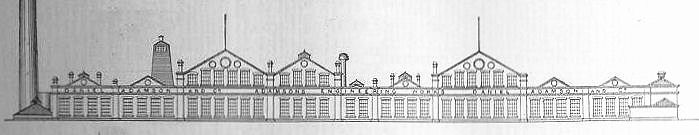

An architects scheme

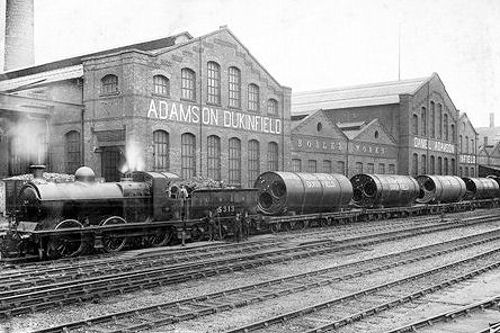

Photograph found via a Tameside Labour Party web-page.

Note the train load of Lancashire boilers

Thanks due to Councillor John Taylor, 28 June 2010 of Tamesside, Cheshire, England, U.K.

Reference only, for the railway buffs :

The locomotive leading this train looks like an L.N.E.R. Robinson J11 .

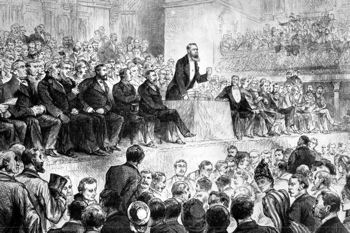

1882 June 27 Daniel, at his home The Towers, Didsbury [link], was host of 76 influential guests, including some of the wealthiest and shrewest men in Manchester. It was the historic occasion upon which the decision to go ahead with the Ship Canal was made.

1885 August 8 a Saturday. Following the passing of the Ship Canal Act, Daniel the chief promoter of the Bill returned from Parliament to Didsbury. The reception he received from the people of Stockport and Didsbury is the stuff of legends. (see an account of this event here) My grandmother told me in the 1940s that aged 9 she was a guest at The Towers on that day, and I guess, probably in the company of her own grandmother Elizabeth Dent , who was Daniel's sister.

[5]

[5]Grave of Daniel Adamson, in Southern Cemetery, Manchester

The white memorial to the left, stands over the grave of Sir John Alcock, aviator.

1894 May 21 The Manchester Ship Canal was opened by Queen Victoria.

DANIEL

ADAMSON 1820 -1890

The following was

composed by The

Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society for

inclusion in the Annual Report of

Manchester City Council of 1890.

The name of DANIEL

ADAMSON,

which will be long remembered in

connection with the Manchester

Ship Canal, is also assured a place amongst the distinguished engineers

by the

part which he took

in the development of steam engineering and the use of

steel. Born at Shildon, in 1818 (sic),

Adamson became apprenticed, when seventeen years old, to the celebrated

T.

Hackworth, at the Stockton and Darlington Railway. After

serving here for six years, he was

appointed managing draughtsman and superintendent engineer to the same

company.

This post he held until 1847, when he became manager of the Shildon

works, also

belonging to this Company. In 1849 he

left the service of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, and after

holding for

a short period the position of manager to the Heaton Foundry,

Stockport, he in

1851, commenced business on his own account as Engineer and Boiler

Maker, at

Newton Moor Iron Works, near Manchester.

About this time he inaugurated a series of reforms and improvements in

the construction and manufacture of steam boilers, with which his name

has

become associated. The first of these

consisted in the introduction of the flanged seam for flue tubes, to

replace

the ordinary lap ring seam which was then generally used.

According to Adamson’s method, the flue tubes

are

made in welded sections, the ends of which are provided with a flange

having a radius of one inch to one and a quarter inches in the

bend. Between the two flanges a hoop of flat plate

is placed, and the seams are riveted up by rivets passing through the

flange of

one ring, the hoop, and the flange of the next ring. The seam

thus formed not only adds enormously

to the strength of the tube in resisting

collapse, but also completely overcame the difficulties which had been

previously experienced through the effect of the expansion of the flue

tubes

bulging the end plates. Adamson in 1852

patented this device, which in later years has been generally adopted,

and

still forms one of the features of Lancashire boilers.

Adamson early recognised the part

which steel was destined to play in engineering construction, and

successfully

carried through its application in the manufacture of

boilers. It appears that his application of steel

began about 1857 (Proceedings Iron and Steel Institute, 1879, p.113),

in making

a locomotive for Messrs Talabot, of Paris, to haul iron-stone from the

Bonner

mines in Algeria to the coast. Only puddled

steel could then be got sufficiently ductile, and that was produced at

the

Mersey Steel and Iron Works Company’s works at

Liverpool. About that time Mr. Bessemer patented his

famous process for steel manufacture, and Mr. Adamson at once prepared

to use

the new material for boiler making, and in 1860 he made the first

Bessemer

steel boilers for Messrs Platt Bros., of

Oldham.

These boilers were 30 feet long by 7 feet 6 inches

diameter, and were made of plates only 5/16ths thick for working at a

pressure

of 80lb. ; no better proof of the thoroughness with which Mr. Adamson

completed

his task can be give than the fact that these identical boilers have

remained

in use to this day. But in spite of

Adamson’s strong advocacy of the new material, it was very

little used by

others for many years, chiefly because it was found too unreliable,

owing to

want of knowledge in the choice of treatment

of the metal. Originally, steel of

tensile strength of forty tons to the square inch was used, but

complete

success was not obtained until a milder variety having a tensile

strength of

thirty to thirty two tons, with 20% elongation was adopted, whereas

now-a-days,

in the best practice, engineers are content with a strength of 24 to 28

tons

per sq. inch, and an elongation of not less than 20% in a length of ten

inches. Steel plates made by the Bessemer

or Siemens process, as are not only stronger, but more uniform in

quality than

iron, they are practically not liable to blistering or lamination as

were even

the best iron plates, and they are tougher and more ductile and even

less

liable to deterioration in work than iron plates. In all

first-class boiler work steel plates

are now practically used, to the exclusion of iron.

When steel was first used, it was

found that the plates were seriously damaged by the operation of

punching the

rivet holes, and, to overcome this difficulty, Adamson in 1862

introduced the

method of drilling holes, to avoid distressing the plates. On

Mr. Adamson’s plan, the plates are bent to

their final form, and the holes are drilled through the plates when in

the

position they will occupy in the finished state. The plates

are then taken apart, the burrs

formed by drilling removed, and the plates and seams riveted

up. In this way the holes fall quite true and

fair when brought together, thus avoiding all such drifting as was

customary

with the punched holes to the detriment of the plate. The

holes also being true, each rivet

completely fills its hole, and takes up its proper proportion of the

stress,

whereas in the rough and irregular surfaces of the punched holes, some

rivets

might be taking an undue share of the strain, thus causing rupture at a

point

below the strength of the seam taken generally.

Thus the seam is strengthened and made more reliable, it is less liable

to leakage, the material is better utilised, and the work is altogether

better

and more neatly finished.

These three improvements which

Daniel Adamson has been prominent in bringing forward are the

characteristics

of the modern stationary type of boiler in this country, which is

constructed

for working pressures up to 200lbs. per square inch, and it would

appear that

Mr. Adamson has scarcely received a proportionate amount of credit for

these

important achievements. Moreover when

Adamson commenced boiler making the manufacture of stationary boilers

was

carried on upon the rudest rule of thumb methods, and Adamson was the

first to

bring the system into the construction and manufacture of these boilers

by

proportioning all parts with a careful regard to the forces to be

met. In this way he not only greatly reduced the

weight of the boilers in proportion to their strength, but having

recognised

the economic advantages of using steam at high pressure, he set about

to

construct boilers for pressures greatly in excess of those then in

vogue, and,

as early as 1855, he had made a boiler and engine which worked

successfully

with a steam pressure of 150lbs. Ever

since the theory of multiple expansion was propounded, he was a firm

believer

in the principle, and in 1861, he made the first quadruple expansion

engine

ever constructed.

In the investigation of the

metallurgy of iron and steel, Adamson took a leading part, and few men

could

boast of a more intimate acquaintance with the properties of these

metals based

on experience. Some idea of the amount

of labour Mr. Adamson bestowed upon the investigation of the mechanical

properties

of iron and steel, may be formed from his own remark that up to 1869 he

had

tested from 30,000 to 40,000 specimens of steel suitable for boiler

plates. Not only were his tests more

thorough and complete than any which had preceded them, but he also

made a chemical

analysis of all samples tested, and was amongst the first to make

practical use

of chemical analysis for ascertaining the mechanical properties of iron

and

steel. Adamson proved by his experiments that it was possible to obtain

qualities of mild steel which would be superior to the best iron for

bridge

building and other structures, as well as for boiler work, and in this

way he

aided materially in bringing about the more extended use of steel in

place of

iron. In the early days of steel great

difficulty was also experienced in welding the new material, and

Adamson was

the first to point out the conditions under which successful welding

was

possible.

Mr. Adamson also took an

extremely active part in opening out the Lincolnshire iron fields, and

he was

the first to erect a furnace at Frodingham, in 1866, depending entirely

on its

supplies upon ores found in the district.

The greatest difficulty was, however, in working the ore, as it could

not be fused at the usual temperature of the blast furnace, owing to

the

presence of a large quantity of lime mixed with the ore, and a want of

silica

and alumina. This experience was gained

at great cost, but the difficulty was ultimately overcome by the

addition of

Lincoln siliceous ore, which is combined with a large quantity of

alumina, and

these works have since been very prosperous.

It yet remains to refer to the

crowning work of Adamson’s life, which consisted of rescuing

the Manchester

Ship Canal scheme, and rendering it a practically possible

undertaking. It is a thrice-told story how Adamson, by

force of argument, succeeded in arousing the enthusiasm of the teeming

millions

of Lancashire workers in support of the great scheme, how bravely he

fought the

parliamentary battle in the face of the opposition of the greatest

vested in

the Empire, how the reverses which would have sufficed to paralyse the

powers

of less sturdy men only served to spur Adamson on to renewed efforts,

and how

he finally led the scheme to triumphant victory.

In the great popular agitation

which carried the Ship Canal Bill, Adamson was the chief actor, but

finding

himself less successful in dealing with the financial difficulties he

retired,

leaving others to carry out the work. In

the course of a few years this great monument to the ability and energy

of Mr.

Adamson will be completed, and it is matter of the deepest regret that

he

should not have been spared to see the accomplishment of the great work.

Mr. Adamson took an active share

in the work of the leading technical societies, at the meetings of

which he was

a regular attendant and frequent speaker.

In 1877 he was elected a member of the Institute of Civil

Engineers. In 1888, the Iron and Steel

Institute gave expression to their high opinion of his merits by

electing him

their President, and in the same year he was presented with the

Bessemer Gold

Medal of that body. He was elected a

member of The Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society in 1881,

under the

Presidency of Mr. Binney.

End of this Obituary

________________________

[4] A further obituary transcription may be seen via this link > > Manchester Faces and Places

________________________

[1] "Daniel Adamson, Shildon, 1778 - 1832" by Frank Hutchinson, at Shildon Library. This slim pamplet of 16-A5 sides, describes the nest into which the young Daniel was born

[2] U.K., BMD copy certificates in possession of the webmaster.

[3] Baptisms at the parish church of Newton in Longdendale, in the County of Chester.

[4] Obituaries discovered by Mrs Ivy Dolan, a descendant of one of Mr Adamson's sisters.

[5] Grave memorial photo credit

[6] In Robert Young's book, below. See "Foreward to the 1975 edition".

[7] Residence in 1861 gleaned from the Census. The assumption of 'Goodier House' gleaned from http://hydonian.blogspot.co.uk/2012/04/goodier-house-victoria-street.html

Further reading / URL linking :

Daniel Adamson web page at Wikipedia

MANCHESTER'S SHIP CANAL - THE BIG DITCH, by Cyril J Wood

TIMOTHY HACKWORTH - AND THE LOCOMOTIVE, by Robert Young (Many references to the Adamsons of Shildon)

A CRUISE ALONG THE MANCHESTER SHIP CANAL, by Colin Wilkinson. ISBN 9781904438922

General Notes

a) The town of Hyde had the benefit of another firm of boilermakers. Joseph Adamson & Co. Ltd. The proprieter J.A. also grew up in Shildon and was the son of Daniel's elder brother John, an N.E.R. engine driver. Joseph's son Dr. Daniel Adamson, became a President of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers.

.

.![Contact post[at]g4fas.net](email.jpg) .

.

© 2008 - 2014 Geoffrey Royle